13. Ownership and lifecycle

Before we jump into the lifecycle operations, let’s understand the concept of ownership of references.

13.1. Pass by value and pass by reference

We have two ways to pass something to a function or method. One is pass by value and the other is pass by reference.

We call something as passed by value when the actual value of a variable is passed to the function, which results in the value being copied to the callee function’s argument. In this case the callee has its own copy and the caller has another copy. If the callee function changes the value, it is not reflected in the caller. In Mojo the data types that fit within the registers of the CPU are passed by default as values and so the callee gets a copy of the value. Also, when we perform an assignment of a variable to another variable, the value of the variable is copied to the assignee.

The second way is to pass the location where the value is stored. In this case, both the caller and the callee refers to the exact same location of the value. We can say that the caller is passing a reference to the value to the callee. So if the callee changes the value, that change will be reflected immediately in the caller.

When we pass a value by reference to a function, that function can potentially change the value. However, if the caller is not expecting its value to be changed while the callee changes the value, we end up with defects. In many programming languages that support pass by reference, it is a common source of defects. So how can we indicate to the caller of a function that the function intends to only read the value or it intends to change it? Mojo provides a solution by annotating the function arguments with a set of keywords that shows the intend.

13.2. read

The read keyword indicates that the argument is used only to read the value and the argument’s value will not be changed. This is the default behavior of all Mojo function’s arguments, so the read keyword is not necessary to be given.

When an argument is marked as read, the Mojo compiler prevents any mutation of the argument’s value. It also does not allow the binding of the argument to be changed as it would have led to discarding (and destruction) of the original value contained in the argument. Since we are borrowing the value, the caller would not expect the value to be destroyed.

fn value_read(read val: Int):

...

fn value(val: Int): # This is also read

...13.3. var

The var in the function parameter indicates that the function assumes the ownership of the given reference argument. This means that we are free to mutate or destruct the passed value within that function.

When an argument is owned, the function can be sure that it can mutate the argument. It is possible that Mojo passes a copy of the value to the function in such cases. When the value is copied, then the caller has own copy and the callee function has its own copy.

fn value_owned(var val: Int):

...13.4. mut

The mut keyword indicates that the function will potentially mutate the value within the passed reference. The difference from var references is that while var arguments may get copied as needed, the mut arguments are not copied.

fn value_mut(mut val: Int):

...13.5. out

The out keyword indicates that the function will initialize a value into the passed reference. The out arguments are implicitly returned by the function. That is, the function cannot return an uninitialized out argument. The caller of the function that takes out arguments will allocate a store for the callee and pass it to the callee. The callee will then initialize the value into the store. The callee does not need to return the value, as the value is already stored in the location passed by the caller. This is sometimes useful when we want to improve performance by avoiding moving or copying the value on return.

fn value_out(out val: Int):

val = 10Usage:

print(value_out()) # Prints 10Note that at the usage site, we are not passing any argument to the function value_out. The compiler instead allocates a storage for the value and passes that storage location to the function value_out. The function value_out then initializes the value into the storage location. The value is then available to the caller at the location passed to the function.

Let’s now look into the lifecycle methods. We start with one that we are already familiar with: the init method.

13.6. __init__

The init method is part of the lifecycle of a struct. The main purpose of init is to initialize all its member variables (a.k.a fields).

from memory import UnsafePointer

struct MyNumber(ImplicitlyCopyable):

var value_ptr: UnsafePointer[Int, MutAnyOrigin]

fn __init__(out self, value: Int):

self.value_ptr = alloc[Int](1)

self.value_ptr.init_pointee_move(value)

fn value(self) -> Int:

return self.value_ptr[]

fn change_value(self, value: Int):

self.value_ptr.init_pointee_move(value) var num: MyNumber = MyNumber(42)

print("num:", num.value())In this example, we defined a struct and the init method within it. The first argument of the init method is always self with a modifier out. The self is a reference to the struct’s own instance that is going to be created. The out tells the compiler that the self is to be initiated and returned by the method (i.e., we can change the field values held within self and self is returned). In Mojo, the function arguments are by default read-only, and we cannot change the values of the function argument. The out is needed for self so that we are able to initialize the fields within the struct. Since one of the main responsibility of init is to initialize the fields of the struct and return it, we naturally need to mark it as out. This implies that the init method is like a static method on Self, that returns an instance of Self.

In the example, we are allocating memory from the heap to store an integer value using the static method call UnsafePointer[Int].alloc. We store a value into the pointer location using the method init_pointee_move on the UnsafePointer. We retrieve the stored value from the pointer using the deference operator [].

13.7. __del__

The delete method del is also part of the lifecycle of a struct. If the init method is used to initialize variables or to allocate resources for that struct, the delete method is used to release the resources held for that struct. For example, if init method allocates memory from the heap, the delete method is used to free that memory. The del method is called just before the value is going to be destroyed by the compiler. If we allocate resources in the init method and do not release or free those resources in the delete method, we end up with resource leaks such as memory leaks. So great care must be taken to symmetrically allocate and free resources using the init and delete methods. You may have noticed that the self argument of the del method is marked with the deinit keyword. This indicates that the value is about to be destroyed.

from memory import UnsafePointer

struct MyNumber(ImplicitlyCopyable):

var value_ptr: UnsafePointer[Int, MutAnyOrigin]

fn __init__(out self, value: Int):

self.value_ptr = alloc[Int](1)

self.value_ptr.init_pointee_move(value)

fn value(self) -> Int:

return self.value_ptr[]

fn change_value(self, value: Int):

self.value_ptr.init_pointee_move(value) fn __del__(deinit self):

self.value_ptr.destroy_pointee()

self.value_ptr.free() var num: MyNumber = MyNumber(42)

print("num:", num.value())Please note that deinit also works for normal methods, only condition being that deinit is applied on self argument. Those methods then act as a destructor.

13.7.1. Eager destruction

Unlike many other languages, Mojo has an eager destruction approach. This means that a value or object is destroyed as soon as its last use is over. This is in contrast with many system languages where the values or objects are destroyed at the end of the scope of a given block. This approach allowed Mojo to have a much simpler lifecycle management, improving overall ergonomics of the language.

The eager destruction might sometimes surprise us while debugging Mojo programs as the variable references would already have been destructed if they are no longer being referenced at locations past the debug breakpoint. A common pattern to extend the lifetime of the value is by assigning it to _.

var a_value: MyNumber = MyNumber(1)

print("Hello")

...

print("World")

_ = a_value # Keep the life of a_value until this point13.8. __copyinit__

Mojo invokes the copyinit for all the cases where a value needs to be implicitely copied. For example, when a variable is assigned to another one, the copyinit may be called for the assignee. This method is quite similar to the init method in the sense that it initializes the struct. In contrast to init, copyinit gets an additional argument of the same type as the struct in which the method is declared (the type of itself is named as Self in Mojo). In the copyinit it is expected that you initialize your member fields with values copied from the "other" struct. copyinit is also known as copy constructor in other languages.

In order to ensure that developers do not accidently copy large values, Mojo requires explicit declaration of the trait ImplicitlyCopyable on the struct to enable copy semantics. By explicitly declaring the trait, the developer indicates that it is safe to copy the struct.

Mojo compiler tries to optimize away copies as much as possible, especially where the reference is not being used later on.

from memory import UnsafePointer

struct MyNumber(ImplicitlyCopyable):

var value_ptr: UnsafePointer[Int, MutAnyOrigin]

fn __init__(out self, value: Int):

self.value_ptr = alloc[Int](1)

self.value_ptr.init_pointee_move(value)

fn value(self) -> Int:

return self.value_ptr[]

fn change_value(self, value: Int):

self.value_ptr.init_pointee_move(value) fn __copyinit__(out self, other: Self):

self.value_ptr = alloc[Int](1)

self.value_ptr.init_pointee_copy(other.value())

print("Copying MyNumber") var num: MyNumber = MyNumber(42)

print("num:", num.value()) var other_num: MyNumber = num # Calling __copyinit__ on other_num

print("other_num after copy:", other_num.value())

other_num.change_value(84)

print("other_num after change:", other_num.value())

print("num after copy:", num.value())In the previous code listing, within the copyinit, we are allocating new memory for holding the copy of the value from other. The other has type Self, which means the same type as the struct defining the copyinit - in this case MyNumber.

Mojo compiler generates a default implementation of copyinit if the struct implements the ImplicitlyCopyable trait. The same goes for Copyable trait - it will generate copy() method for you. Most of the time this is suffucient, unless your struct holds resources that need special handling during copy.

struct A(ImplicitlyCopyable):

var val: Int

fn __init__(out self, v: Int):

self.val = vUsage:

var a1: A = A(10)

var a2: A = a1 # This will invoke the auto-generated __copyinit__

print("a1.val:", a1.val) # Outputs: a1.val: 10

print("a2.val:", a2.val) # Outputs: a2.val: 1013.9. __moveinit__

Mojo invokes the moveinit for cases where a value needs to be physically moved. This method is quite similar to the init method in the sense that it initializes the struct. In contrast to copyinit, moveinit has the second argument annotated with deinit. The deinit is required because the second argument’s value will be destroyed once the move operation completes. In moveinit, we reassign the values from the other struct to the struct which defines the moveinit.

One thing to note is that the moveinit may not be always called when a value is "moved" (even when using the transfer ^ operator). You can think of move as a transfer of ownership, but sometimes the compiler is not able to optimize it to a simple transfer of ownership (logical move), instead needs to copy the value to a new location and clear the old location (physical move). Physical move happens for example when a value is moving from a short-lived stack frame to a longer lived one.

Move operations are particularly useful for cases where copy operations are expensive. For example, in Mojo move semantics are used for String. This ensures that the string operations are as much efficient as possible.

To indicate a transfer of ownership, the caret ^ operator is used. The caret operator is more of a hint to the compiler that we want to transfer the ownership of the value. The compiler may still decide to copy the value instead of moving, if it thinks copying is more optimal.

fn __moveinit__(out self, deinit other: Self):

print("Moving MyNumber")

self.value_ptr = other.value_ptr var num: MyNumber = MyNumber(42)

print("num:", num.value()) var other_num2: MyNumber = num^ # Moving

print("other_num2 after move:", other_num2.value())

other_num2.change_value(84)

print("other_num2 after change:", other_num2.value())

# Uncommenting below line results in compiler error as `num` is no longer initialized

#print("num after copy:", num.value())Due to the fact that Mojo compiler decides when to physically copy or move, we cannot make assumptions on when the moveinit and copyinit are actually called.

Mojo requires explicit declaration of the trait Movable to enable move semantics. Mojo compiler generates a default implementation of moveinit if the struct implements the Movable trait. Most of the time this is suffucient, unless your struct holds resources that need special handling during move.

If your struct implements ImplicitlyCopyable, then Movable is implemented automatically (ImplicitlyCopyable implements the Movable trait); this is useful because Mojo compiler can sometimes optimize copy to move.

struct B(Movable):

var val: Int

fn __init__(out self, v: Int):

self.val = vUsage:

var b1: B = B(20)

var b2: B = b1^ # This will invoke the auto-generated __moveinit__

print("b2.val:", b2.val) # Outputs: b2.val: 20

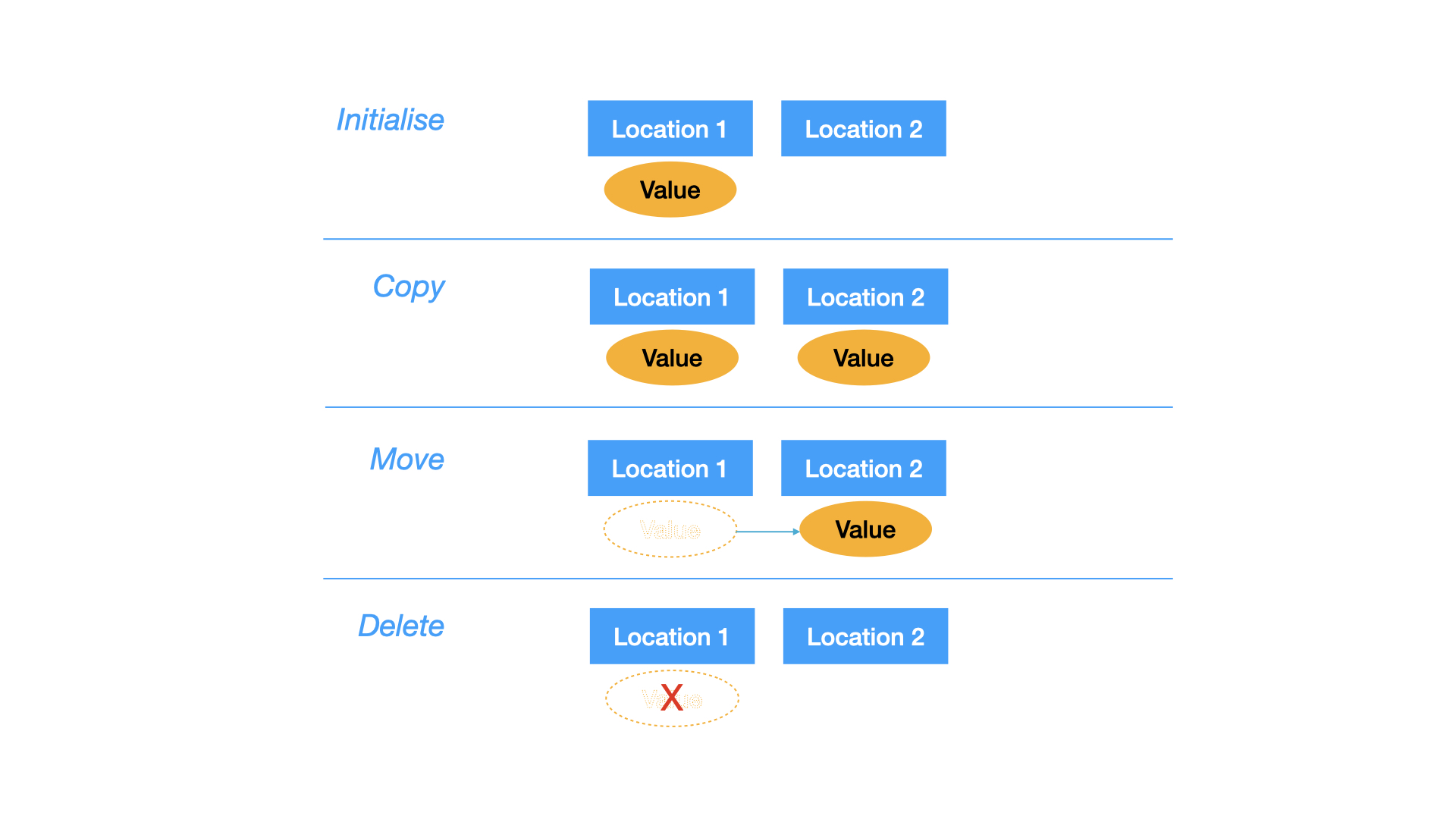

# print("b1.val:", b1.val) # This would be an error since b1 has been movedThe different lifecycle operations are illustrated in the following diagram.

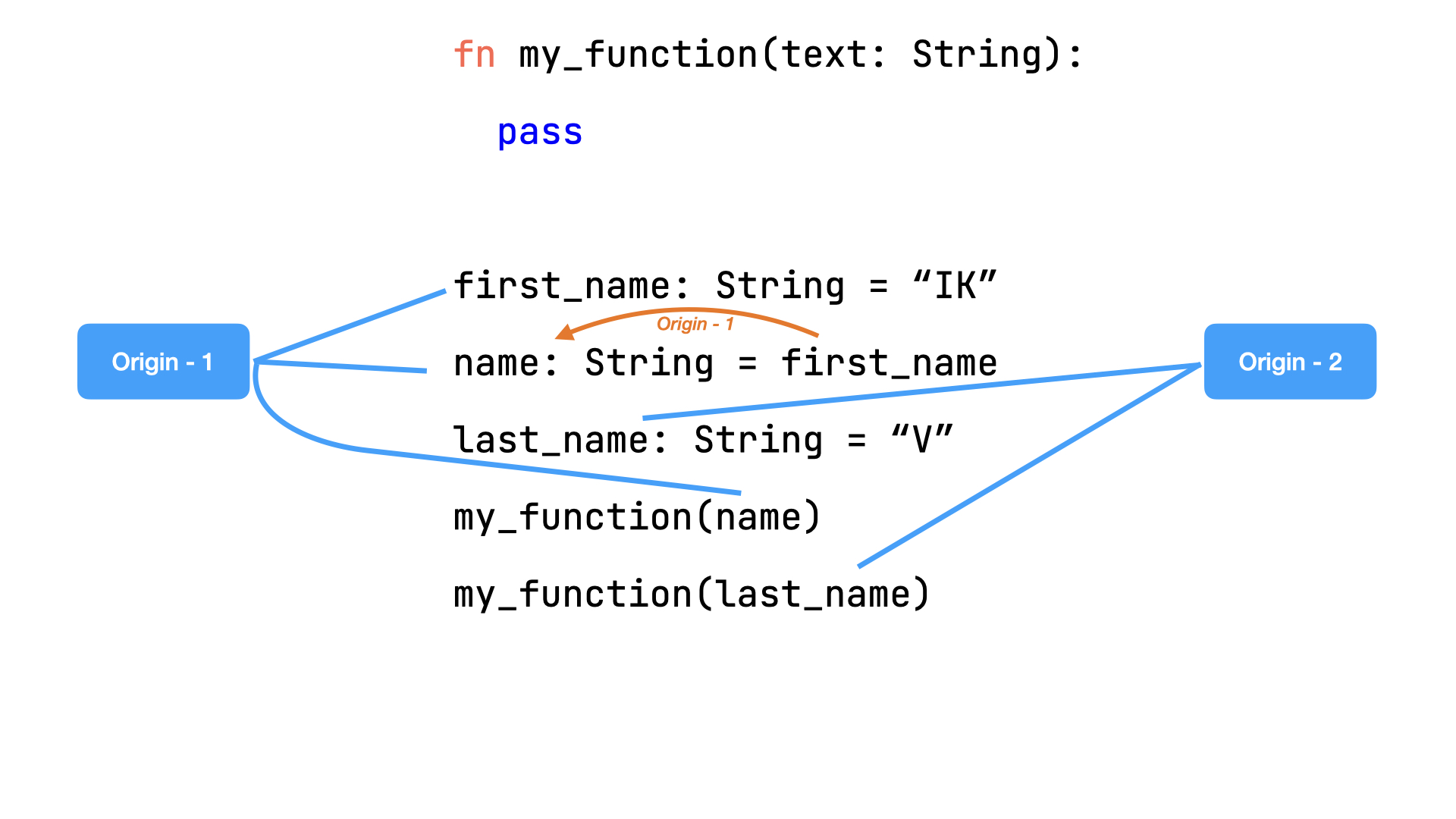

13.10. Origin

We saw earlier how Mojo destructs values eagerly. This means that as soon as a value is no longer referenced, it is destroyed. How does Mojo know when a value is no longer referenced? In order to track the references to a value, Mojo uses the concept of origin. Each value has an origin associated with it indicating the variable that originally owns it. This origin is tracked by the compiler. When a variable is assigned a value, it is associated with an origin. When that value is assigned to another variable, the same origin is associated with the new variable. When a value is passed to a function, the same origin is associated with the function argument. Most of these tracking is done transparently at the compile time by the compiler. However, there are some cases where the developer needs to explicitly indicate the origin of a value. This happens when there is an indirection involved, such as when using pointers or references.

When a value is no longer used, the origin tracking indicates that the value can be destroyed. This is how Mojo ensures that values are destroyed eagerly and resources are freed as soon as they are no longer needed. In a way, the origin association increases the lifetime of a value, instead of the traditional block scope based lifetime management.

Origin in Mojo is represented using the Origin struct. The Origin struct is a special struct that is used to track the origin of a value. There are two types of origin (those are actually concrete comptime values of the struct Origin): immutable origin represented by ImmutOrigin and mutable origin represented by MutOrigin. The immutable origin is used for values that are not expected to change, while the mutable origin is used for values that can change.

struct A:

var value: Int

fn __init__(out self, value: Int):

self.value = value

fn set_value(mut self, value: Int):

self.value = value

fn my_function(a: A):

passUsage:

ten: A = A(10)

my_function(ten)In the above example, the origin is being tracked by the compiler, but we do not have to explicitely mark the origins.

However, take a look at the following example where we try to modify a value passed to a function.

fn my_function_modify_wrong(a: A):

# a.set_value(20) # Uncommenting this line will cause a compile-time error

...Usage:

# my_function_modify_wrong(ten) # Uncommenting this line will cause a compile-time errorUncommenting the above code will cause a compile-time error, because we are trying to modify a value in a function that takes an immutable origin argument by default.

The following code listing will compile correctly, because we are explicitely marking the origin as mutable using the MutOrigin type and marking the argument as a reference with mutable origin using the ref[o] syntax.

fn my_function_modify[o: MutOrigin](ref[o] a: A):

a.set_value(20)

print(a.value)Usage:

my_function_modify(ten)Here we are taking a parameter that is of type MutOrigin. This parameter is then used in ref which represents a reference. Together the ref[o] syntax indicates that we are passing a reference with origin o. Since o is of type MutOrigin, we are allowed to modify the value within the function. You will learn the ref syntax in a later chapter.

Note: Mojo allows a short-hand syntax mut for mutable references in function arguments.

13.10.1. origin_of

In some cases, we may want to explicitely get the origin of a value. This can be done using the origin_of function. For example, we may want to share a pointer to a value, and to ensure that the pointer always points to a valid value, we need to align the origin of the pointer with the origin of the value.

struct B(ImplicitlyCopyable):

fn __init__(out self):

pass

struct A:

var value: B

fn __init__(out self, value: B):

self.value = value

fn get_pointer(self) -> Pointer[B, origin_of(self.value)]:

return Pointer(to=self.value)Usage:

b: B = B()

a: A = A(b)

_ = a.get_pointer()In the above code listing, we have a struct A that holds a value of type B. In the get_pointer method, we are returning a pointer to the value held within the struct. In order to ensure that the pointer is valid as long as the value is valid, we are using the origin_of function to get the origin of the value and passing it to the Pointer type. This ensures that the pointer’s origin is aligned with the value’s origin. Without using the origin_of, the compiler cannot automatically infer the correct origin and will raise a compile-time error.

Sometimes we may want to define a struct that holds a reference with a specific origin. This can be done by defining the struct with a type parameter that represents the origin and use that type parameter to define the origin of the reference within the struct.

struct ARef[o: Origin]:

var p: Pointer[String, origin=Self.o]

fn __init__(out self, p: Pointer[String, origin=Self.o]):

self.p = pUsage:

var value = String("Hello")

var val_ref: ARef[o=origin_of(value)] = ARef(Pointer(to=value))

print(val_ref.p[]) # Prints "Hello"In the above example, within ARef, we are holding a pointer to a value we get from outside. In order to ensure that the pointer is valid as long as the value is valid, we need to ensure that the origin of ARef is same as the origin of the value being pointed to. This is done by defining a type parameter o of type Origin for the struct ARef, and using that type parameter to define the origin of the pointer within the struct. When we create an instance of ARef, we need to provide the correct origin using the origin_of function to ensure that the pointer is valid. As you can see, the origin_of function brings clarity to which value’s origin we are referring to.

13.11. Linear types

In Mojo, when we define a struct and we do not provide a __del__ method, then the compiler creates the destructor automatically for us. Most of the time this is the desired behavior. However, there are cases where we want to have more control over the lifecycle of a struct. For example, we may want to ensure that a struct is used only once and then destroyed. This is where linear types come into play.

A linear type is a type that can be used only once. This means that once a value of a linear type is used, it cannot be used again. This is useful for ensuring that resources are not leaked and are properly released when they are no longer needed. This means a linear type cannot be copied or moved. The destruction of a linear type must be explicit and not just because it goes out-of-scope.

In Mojo, copy and move are already explicitely opted-in. You can additionally place @explicit_destroy decorator to a struct to make it a linear type.

@explicit_destroy

struct Linear:

var value: Int

fn __init__(out self, value: Int):

self.value = value

fn destroy_me(deinit self):

print("Destroying Linear with value: ", self.value)

fn my_function(a: Linear):

passUsage:

l: Linear = Linear(10)

my_function(l)

l^.destroy_me() # Commenting this out will result in a compile-time errorIn the above example, we have defined a struct Linear that is marked with the @explicit_destroy decorator. This indicates that the struct is a linear type. In the main function, we create an instance of the Linear struct and pass it to the my_function. After using the linear type, we explicitly call the destroy_me method to destroy the linear type. If we do not call the destroy_me method, the compiler will raise a compile-time error indicating that the linear type has not been destroyed. Since we do not implement Movable or ImplicitlyCopyable traits for the Linear struct, the compiler will not allow any copy or move operations on it. This ensures that the linear type is used only once and is properly destroyed when no longer needed.

Note that when we either let Mojo create the destructor automatically or we provide our own destructor using __del__, the struct is assumed automatically to implement ImplicitlyDestructible trait. By marking the struct with @explicit_destroy, we are indicating that the struct does not implement ImplicitlyDestructible trait, and hence the destruction must be explicit.

Linear types are useful for managing resources that need to be used in a controlled manner, such as file handles, network connections, or other system resources. By using linear types, we can ensure that these resources are properly released when they are no longer needed, preventing resource leaks and ensuring the stability of our applications. It allows for compiler enforced resource management, reducing the chances of runtime errors related to resource handling.